I swirl the golden liquid in my glass. “Notice the color of the gold añejo,” directs Dr. Adolfo Murillo, the maker of Tequila Alquimia. “Its color comes from oak barrels.” Absent are wedges of lime and shakers of salt that are used to soften the sharp burn of tequila when it travels down the throat. This is tequila made to sip.

He tells me to hold the flavors of the tequila in my mouth and let them steep into my tongue. “We took minerals from deep in the earth, rain water from the sky, energy from the sun and created liquid gold,” I taste the earth, sky and sun before it disappears in a swallow.

Next, Adolfo reaches for a liter of blanco. The colorless tequila swims inside the recycled beveled glass. This tequila could be confused with water, too young to have absorbed the color of oak. How big would the bottle need to grow to hold 65 gallons of water, the water footprint of a liter of tequila?

The water footprint of tequila represents the average fresh water required to grow the agave and distill it into the popular beverage. Each liter has a blue, green and grey water footprint. Color has been assigned to water. Blue water is drawn from lakes, reservoirs and underground supplies. Green water is rainwater. Grey represents the polluted water resulting from the production of a product—in this case tequila. Each brand of tequila has a different water story to tell depending on how the agave is farmed and distilled. The story of Tequila Alquimia begins on a blue agave ranch in the town of Aqua Negra, Jalisco, Mexico. The ranch is owned by a Ventura County native.

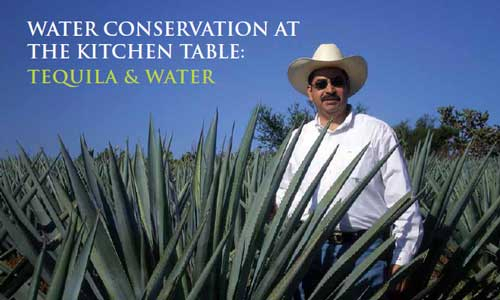

I meet Adolfo at his home. We sit at the dining room table that is bare except for a laptop computer. His neat slacks tell me that he came from his optometry practice. His weathered cowboy boots remind me that the doctor is also a rancher. “What makes your tequila win gold medals?’ I ask as I notice the medals that hang on the far wall. Tequilas reposado, anejo and extra anejo, have collected 13 gold medals between the San Francisco World Spirits Competition and the Chicago Beverage Tasting Institute over the past three years.

“If you treat the earth well it will treat you well. That is what my grandfather told me. The earth treats us with flavorful tequila.” It is his grandfather’s teaching that led him to produce one of only four tequila brands certified USDA organic out of 1,150.

He shows me a video of his 125-acre ranch. The spiny blue agave plants grow in obedient straight lines. The plants are striking. Their strong sharp pose reaches for the blue sky. The stillness of the plants is broken by the movement of cows that wander between the rows.

“The cattle are our weed control. We spray no herbicides,” says Adolfo.

“Don’t the cattle damage the agave plants?” I ask.

“No, that has never been a problem. The Limousine cattle, originally from France was chosen for their superior foraging.”

Neighboring farms rely on the steady application of chemicals to eradicate pests, fungus and weeds. Spent chemicals alter fresh water into grey water. “What makes your plants resistant to pests and fungus without the use of chemicals?”

“Our plants grow naturally and rely on themselves instead of chemicals. They have built their own natural defenses.” Most conventionally grown crops such as wheat or lettuce receive a single season of chemicals. Since agave grows for six to10 years before it is harvested, conventionally grown agave absorbs a decade of chemicals.

The town of Aqua Negra receives little rainfall. The soil does not crumble like moist chocolate cake of rich farmland. The soil is layers of brittle sandstone. The water hides underground. Most agave farms irrigate year-round. Once the plant is established after the first two years Adolfo’s agave is dry farmed utilizing green water.

“How is it that you can dry farm?” I ask.

“We let the weeds grow during the rainy season where they protect the topsoil and help to store the water. We then mow the weeds, leaving the root systems. The mowed weeds incorporate into the soil. This all helps the soil absorb moisture for the plant in the dry months.” The organic material in the soil absorbs and retains moisture. Adolfo’s farm is able to collect millions of gallons of water under the parched rocks.

The health of Adolfo’s agave is demonstrated by the weight and sugar content of the piña, the core of the plant. The piñas are three times the average weight of surrounding farms. Too heavy to carry, weighing 200 pounds or more, they require the assistance of mules to carry the ripe piñas to trucks. The sugar content or brix of the piña adds to the flavor complexity of tequila. The brix for Adolfo’s agave is more than double the average.

Adolfo describes the distillation process. I begin to understand why the name alchemy was chosen as the name for this tequila. “Distillation was invented by ancient alchemists.” The agave is first cooked until it is soft and tastes like sweet potato. It is shredded to release the juice from the plant fibers. In fermentation tanks that stand 15 feet tall, natural yeast eats the sugars and the digestion yields alcohol. “The fermentation will take seven to 10 days when you let it follow its natural course, as we do. Many tequila companies prefer the faster method of three days, using supercharged yeast which is essentially chemical fertilizers.” The heavy metals and salt present in chemical fertilizers is concentrated during distillation.

The tequila leaves behind vinaza, a liquid that holds high concentrations of chemicals, heavy metals, salt and nitrogen. Every one-liter bottle of tequila leaves 10 liters of vinazas. The common practice of vinaza disposal is to pour it untreated into rivers. It turns rivers into brown raw sewage soup. The grey water strips the river’s ability to sustain life. The Mexican government has begun a campaign to encourage distilleries to build treatment plants, by imposing fines. Most distilleries opt to pay the fines and continue dumping the nitrogen-rich vinazas into rivers. Adolfo has devised a solution for the vinaza disposal. “On the land behind the distillery we prepare an area with a layer of clay followed by a layer of piña fiber. We pour vinaza over it. It turns into compost that supports life,” he says, showing me a picture of weeds and flowers growing out of a mound of soil.

Adolfo’s ranch touches the acreage of his grandfather’s former ranch. The new owners of his grandfather’s ranch slurp the water from a spring on the land faster than it can be replenished. The spring will run dry. Chemical herbicides, pesticides and fertilizers taint the spring and the water hidden underground. The fate of his grandfather’s land fuels his passion to teach organic farming. He has trained over 30 Mexican farmers to grow organically. The sip of tequila I hold in my mouth impacts a river thousands of miles away. My tequila choice sends ripples somewhere on the planet. Before my next sip I make a toast, “To Adolfo’s Tequila Alquimia and others who work to preserve the integrity of fresh water supplies on our small blue planet.” The tequila glass chimes in agreement.

For more information about Tequila Alquimia and a list of locations where it is available visit tequilaalquimia.com

You can view this article in Edible Ojai Magazine recent recipient of the James Beard Foundation Award of Excellence.

Love the article and congratulations on its publication in Edible Ojai.