By Hannah Guzik

Originally published in the California Health Report

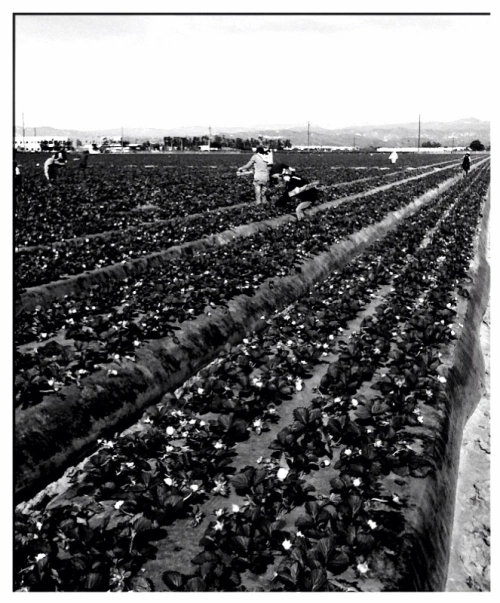

Nearly every afternoon this summer, Florencia Ramirez drove past the strawberries and lima beans growing in the Oxnard plain, and each time she grew angry about what she saw.

As the plants gulped in the Southern California sun, high-powered sprinklers ricocheted over the fields, spraying water into the air during the heat of the day, when evaporation was at its peak.

In an area plagued with water shortages and droughts, some of the largest agricultural producers in the nation seemed to be using water with abandon, Ramirez observed.

“I couldn’t believe it,” she said. “We live in what is technically a desert and I pass thousands of acres of farmland everyday that are wasting a tremendous amount of water.”

The Oxnard resident, who holds a master’s degree in public policy from the University of Chicago, wondered if there was a better way. She began to research agricultural water use and stumbled upon the concept of dry farming — which uses only precipitation to grow crops.

“I found out that even here, amidst all these irrigated farms, there are a few people dry farming, growing wheat, olives, even apricots, with limited water,” she said.

Ramirez, whose friends aptly call her “Flo,” is now turning her anger at water waste into action. She’s writing a book aimed at consumers on how to “Eat Less Water,” a trademark phrase she uses to explain the concept of conserving the natural resource through farming practices and grocery-buying habits.

Dry farming doesn’t work in all locations or for all crops, but it can work successfully even in relatively dry climates, such as Southern California’s, she said. And many of the principles of dry farming, such as paying close attention to the weather and soil composition, can be applied to conventional farming to help save hundreds of thousands of gallons of water a year, Ramirez said. Those plants that require more water, such as lettuce or many vegetables, can be drip irrigated, instead of watered with sprinklers or by flooding a field.

Ramirez says water experts predict that by 2025, two-thirds of the world will be experiencing water scarcity.

“We live in this illusion that we have enough water, but most places, like right here in Oxnard, are experiencing water deficits, which means we are using more than is naturally replenished each year,” she said. “It’s not sustainable.”

The average American household uses 100 to 150 gallons of water daily, a huge amount compared to the four or five gallons an African family uses each day, Ramirez said. “But what we use on a daily basis really is a drop in the bucket compared to industrial use and the virtual water footprint of what we eat, drive and wear, which is 1,100 to 1,300 gallons per day,” she said.

Seven out of every 10 gallons of fresh water on the planet are used to grow food, “so if we’re going to have a true conversation about water usage, we have to talk about what we eat,” Ramirez said.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture’s organic certification doesn’t include any stipulations on water usage, something Ramirez would like to see changed. Read more.

click to Read & Leave a comment

Click to close comments

Comments